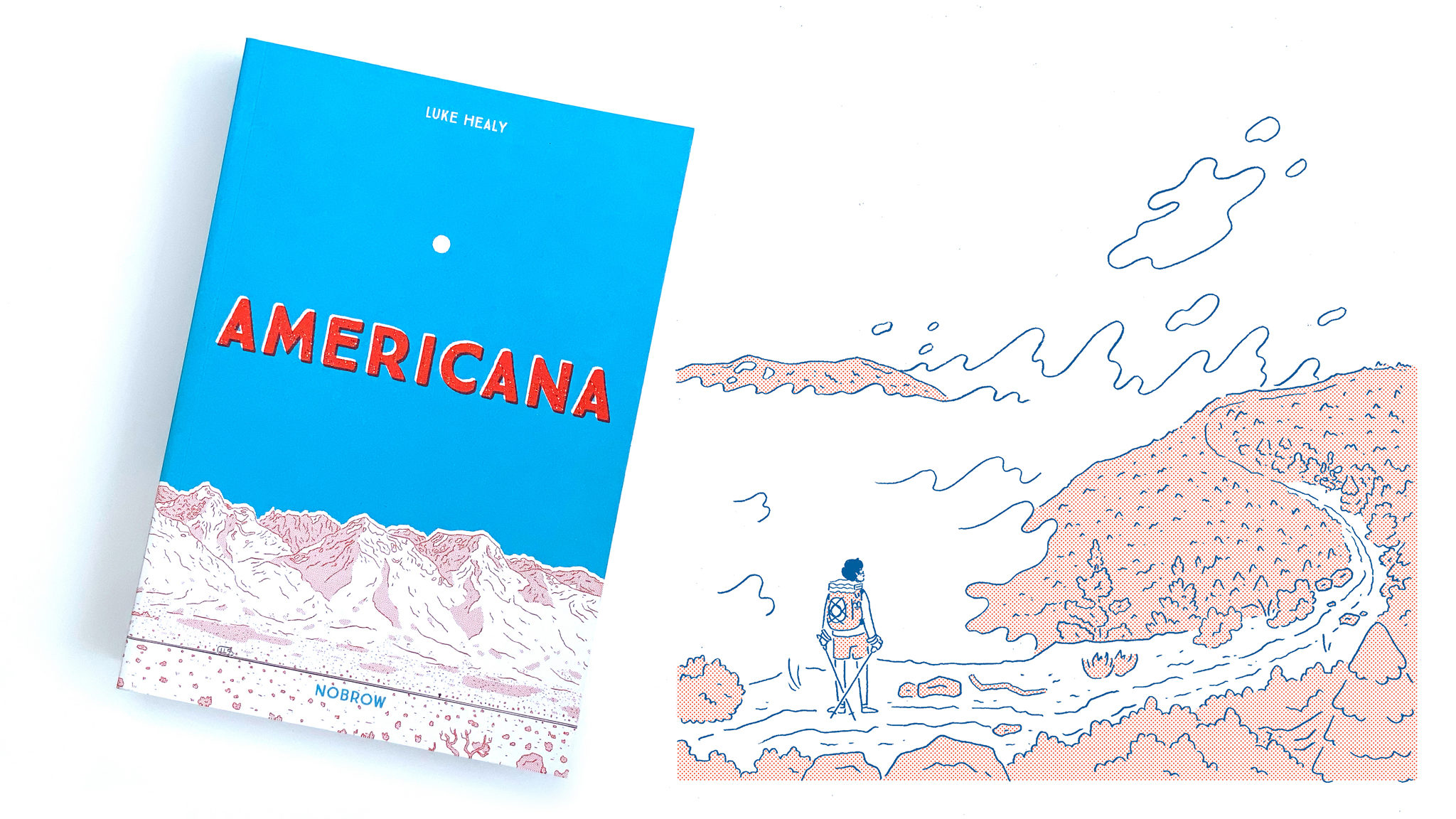

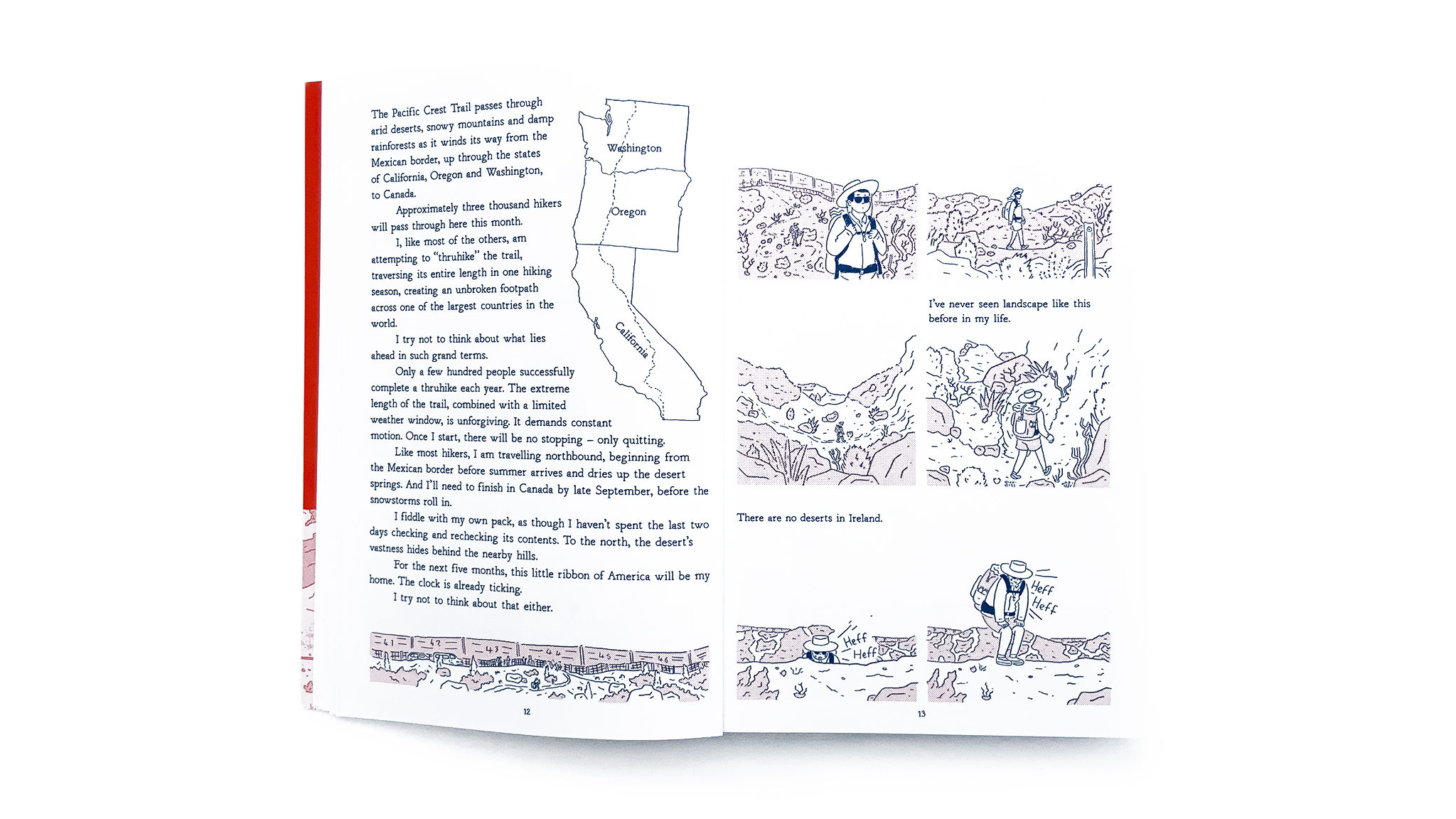

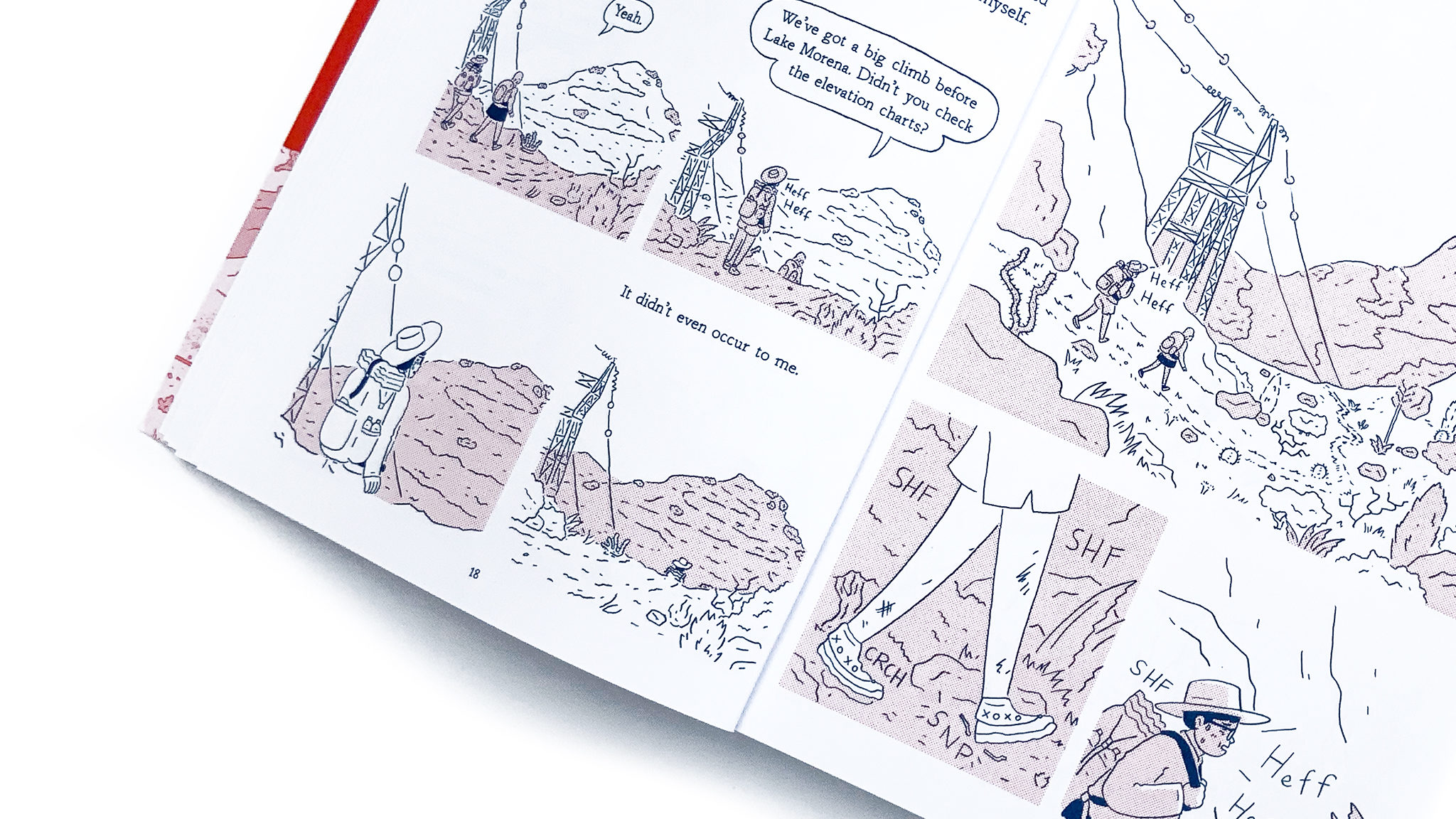

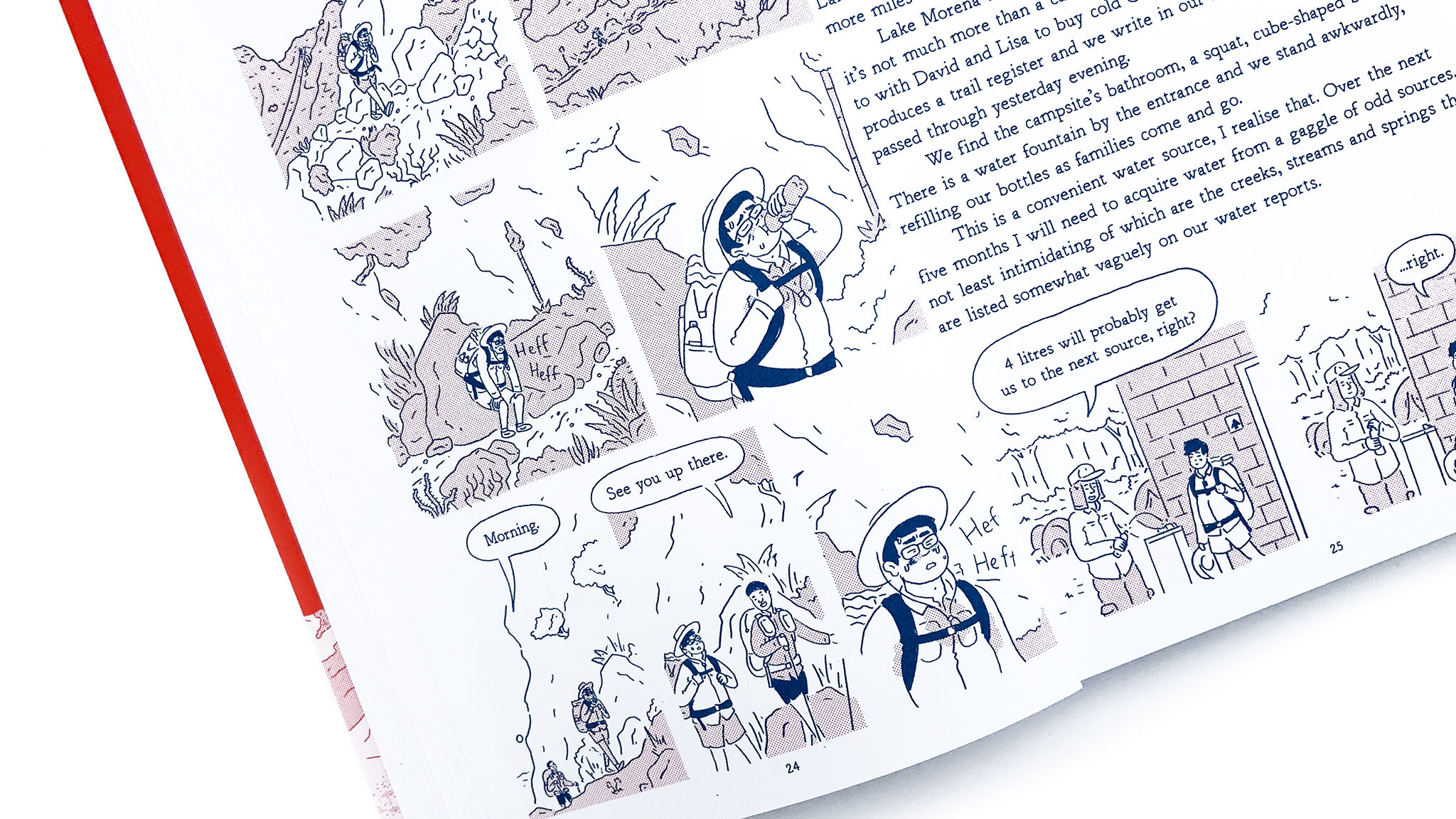

Americana by Luke Healyis a unique book: part travelogue and part memoir it’s a work that effortlessly stitches together multiple narratives across time and place. The main story is more than compelling enough- Luke recounts his 147 day journey across the 2660 mile long Pacific Crest Trail (a staggeringly long hiking path that winds up from America’s desert border with Mexico to Canada’s mountainous one). However this journey is more than just a hike, it is the culmination of a lifelong obsession with the USA that Luke has never quite managed to shake. As he puts it himself:

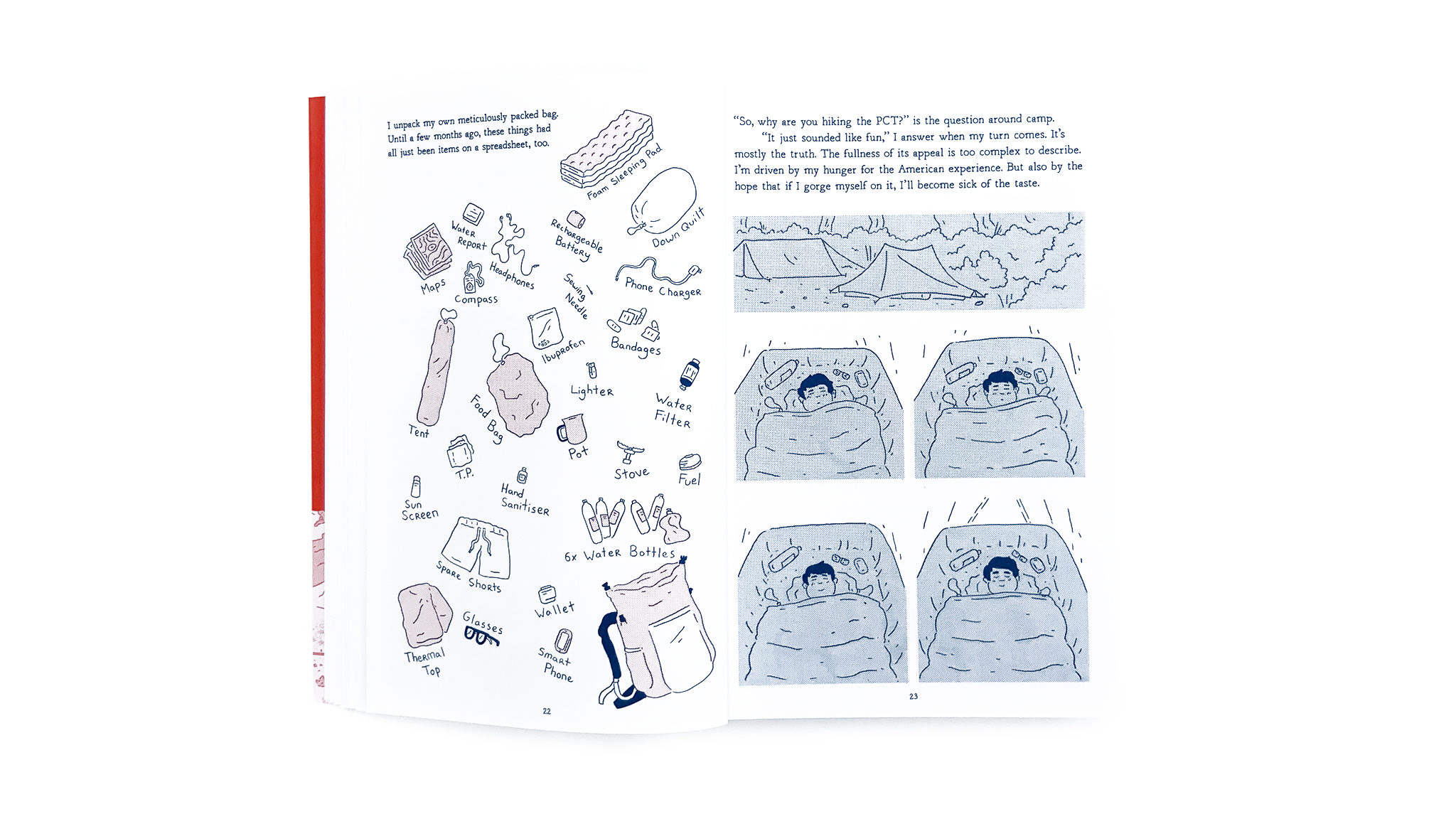

“I’m driven by my hunger for the American experience. But also by the hope that if I gorge myself on it, I’ll become sick of the taste.”

We sat down with Luke to get a deeper insight into why he took on the PCT, and how the book’s concept has developed since he started planning for the trail.

How did you first hear about the PCT, and how long did it take you to prepare for it?

I first heard about the PCT in 2014, when I saw a trailer for the film adaptation of Wild by Cheryl Strayed. I saw it right before I had to move back to Ireland from the USA. I didn’t want to leave, and was in a huge funk. The first thing I did when I returned to Ireland was buy and read Wild. I was immediately obsessed, and decided that I would hike the PCT in 2016, leaving myself enough time to prepare, since I had never hiked, backpacked, or camped before. All told, I prepped for about 18 months.

This is a massive understatement, but the PCT looks really, really hard. You very honestly document the amount of times during the trip that you almost quit the trail. How do you feel not finishing the PCT would have affected you, if at all?

I don’t think I’d have the same kind of closure that I have now about my relationship with the USA. Every time I’d lived there before, I was forced to leave against my will, and it definitely left me feeling as though I had left things unfulfilled. Although my journey wasn’t without compromise (in the form of a few skipped sections), I feel as though when I walked out of the USA, I’d reached the end of something. Though at the time, all I wanted was to sleep indoors again.

What were the most difficult moments along the trail?

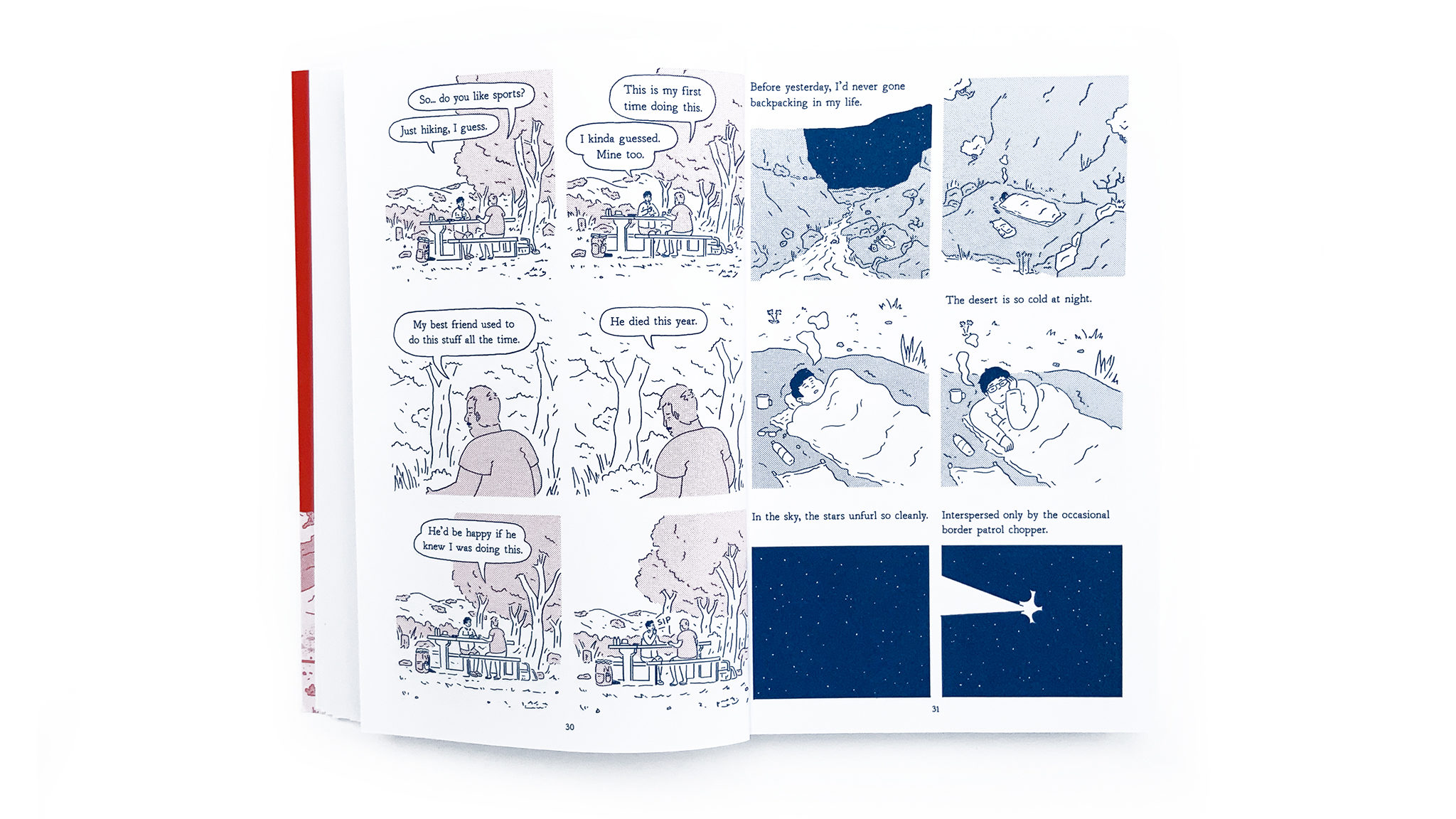

The hardest moment by far, was around mile 340 at Cajon Pass. I’d had a horrible few days, and was suffering from a depressive period. I was so unhappy, and exhausted, and was just plodding along. And I kept running out of water, multiple days in a row; which is obviously very dangerous when you’re isolated and tramping across a blisteringly hot desert. I had a realization, then, that I was engaging in “risky behaviour”, by not taking enough caution with my water supplies. A classic symptom of depression. I decided that if I wasn’t able to take care of myself, I shouldn’t be on the trail, and a few days later I got a ride to L.A. with the intention of quitting for good.

Also, the day I broke my leg along in the mountains was pretty bad. But I just kept taking ibuprofen and hiking on it, so the depression thing was probably worse, haha.

Do you also have any stand out good memories of your time there?

A lot! As hard as the trip was, it was one of the best experiences of my life. Oddly, a moment to really sticks out to me, which actually doesn’t feature in the book because I found it too difficult to communicate, happened right after I’d crossed the state border form California to Oregon, months into the journey. I was in Callaghan’s Lodge, who offered cheap food for hikers –and when you’re hiking the PCT, you are always starving– I was walking through their dining room, and made eye contact with another thruhiker, who was taking the first bite of a huge plate of spaghetti and meatballs. We both started laughing because we both knew how much joy she was getting from that bite, and in that moment we saw how absurd we both were. It felt amazing to be so connected to a complete stranger.

Despite that there seems to be a great deal of community feeling amongst the hikers you met and walked with, a unique kind of hiking culture. Have you kept in touch with any of the people you met along the way?

Yes, I’m still in touch with lots of them, via facebook. But I mostly still talk to the hikers from the group “Mile 55”, who I hiked about 400 miles of trail with. They’re some of the best people I’ve ever met, and I’m extremely grateful to call them my friends. I’m going to be seeing them for the first time since trail in October, and I can’t wait (please attend my US events while I’m there!).

I also have seen Justin and Jenny a few times, the hikers whose wedding I attended on trail. We’ve crossed paths in London, and I am very happy any time I get to see them.

There also seemed to be an impressive amount of support along the way for hikers, people who would offer up their outhouses etc for walkers to sleep in, and leave water caches in the desert near Mexico for them. Do you know anything more about these “trail angels”, or how many of them help maintain the trail?

No official numbers, but my guess would be hundreds. There are pillars of the community who open up their houses every year, but also the dozens of people any hiker meets at road crossings or trail junctions, with cold cans of soda, or hot fresh food ( a rare luxury on trail). Or just the trail angels who don’t even know that’s what they are, who pick you up hitchhiking, and invite you to shower or sleep at their place.

They keep the trail alive, and they’re some of the most generous, incredible people I’ve ever had the privilege to meet. And that’s not even mentioning all of the volunteers who head out and do work on the trail itself, clearing fallen trees, maintaining this massive engineering project that can sometimes look like a simple dirt path, but is unfathomably complicated to maintain over such an enormous distance.

If my walk across America jaded me to certain aspects of US culture, these people, were what reminded me of the other side of that coin.

The amount of detail and small recorded moments that you‘ve captured in Americana is incredible, it almost feels like watching a documentary at times rather than reading a comic. How did you keep a record along the way? Was it all notes, or did you have time to draw occasionally whilst there?

I took no notes, and made no drawings. While hiking, I never intended to write a book about the experience. I just wanted to do something for my own self. When I got home and decided that I did want to put something together, the memories were so visceral that I had no trouble recalling them, I think just because every day was so unusual and unlike anything I’d ever experienced before. Three years later, things have definitely faded a little, so for that reason, I’m very glad I took the time to write the most interesting parts down.

Could you also expand a little more about the process of making the book itself? Did you start it immediately after returning from the US? And are there many extra stories from the trail you ended up editing out?

I started working on it pretty much as soon as I got home to Ireland. I sat down and wrote an outline, as well as a detailed draft of the first hundred or so pages before pitching it to Nobrow. Then over the next 18 months I wrote a bunch of rough drafts of the book.

A lot of stuff got cut. It’s hard to condense five months into something digestible. In the end, I mostly cut stuff that felt like it was detouring too much from the momentum of the overall book. Even though the final book has something of a meandering quality, I still wanted everything to seem purposeful, and some stories were just too unrelated to fit in.

One of my favourite little anecdotes that got cut took place in the town of Mt. Shasta, a very hippy spiritualist kind of spot (it has more than ten crystal shops). While I was there, my bankcard got blocked for a suspicious transaction, and I had no way of contacting my bank because I couldn’t pay for an international call. In the end, I had to borrow $20 from another hiker, and look for a payphone and phone card. I searched all over town. In the end, I found a phone card, buried amongst “bigfoot is real” bumper stickers and “UFO Drivers licences” at a gas station. The gas station owner was surprised when I brought it up to check out and said “that’s probably been there since the ‘90s”. It still worked.

As you describe reaching the end of the PCT during Americana’s last few pages you say you “don’t feel changed. Not yet”. Now time has passed, do you feel the trail has changed you?

We’re all changing constantly, I think. Everything we experience, and every choice we make just influences the trajectory of that change. Without hiking the PCT, I wouldn’t be somehow preserved as the person I was before I hiked it. But I certainly wouldn’t be the same person I am now. Everything in my life is different because of hiking the PCT, and I’m very thankful for that.

The book is of course equally as much about your relationship with America as it is about the hike itself. Do you still feel as such a strong pull to it as you once did?

I don’t. I have many fond memories of my times living in the USA, but I have no desire to live there now. I love my American friends, and any time I can see them is an incredible privilege, but for now, I’ve lost interest in just about everything else the USA has to offer.

And lastly, have you continued hiking as a hobby, or would you take on a similarly large hike again?

I haven’t hiked at all since finishing the PCT, but I’d love to start up again. I spent a lot of this summer in Scotland, and the landscapes here have really reignited my interest in hiking and backpacking.

If funds ever allow, I’d also love to do another large thruhike. Maybe the Via Francigena, a foot path from Canterbury to Rome. Or the Te Araroa, a trial that runs the length of New Zealand. I have my eye on those.

Luke Healy is an Irish cartoonist currently based in London, England.

Americana (And The Act of Getting Over It.) can be purchased from FlyingEyeBooks.com in the UK, and PenguinRandomHouse.com in the US. It is also available in all best bookstores.