Last month, we were thrilled to release the second book from Kate Greenaway Medal winning William Grill, The Wolves of Currumpaw. Where Shackleton’s Journey took us on an epic expedition to the icy antarctic, this time we’re following Ernest Thompson Seton’s true life tale of hunters and the wolves they were hired to trap, set across the vast plains of New Mexico in the dying days of the old west.

After a busy month of launch events, we finally managed to sit down with Will to ask him a few questions for you!

1. Why did you decide to write (and draw) about Lobo and Seton’s story?

As well as being an emotive story, I was struck by how Seton’s tale says something relevant about our relationship to nature today. For me, his experience with Lobo is a good allegory for how regrettable our selfish treatment of nature may be. The tale unfortunately ends with Lobo’s death, but what Seton goes on to do afterwards can be seen to redeem his actions in some way.

2. How do you feel attitudes have changed since Seton’s time?

I think now there is more of an appreciation for nature and we have a deeper understanding of ecology, a concept which didn’t really exist in the late 1800s. In Seton’s time, animals were treated more like a resource and anything that was a nuisance was removed. Thankfully this attitude has changed a great deal, as we understand that many animals like wolves play a vital role in the food chain and deserve to live freely.

The main focus of my story was to show how one man’s attitude towards nature changed, influencing the early conservation movement and the way we treat animals. In a wider sense, I also wanted to show that these destructive early attitudes affected not only wolves but caused extreme suffering to Native Americans, however I am aware that my book in no way represents the full oppression and devastation inflicted upon Native Americans by the European settlers. That would be a whole other book, one that deserves a full story to itself.

3. How did your own research inform your adaptation of Seton’s original story?

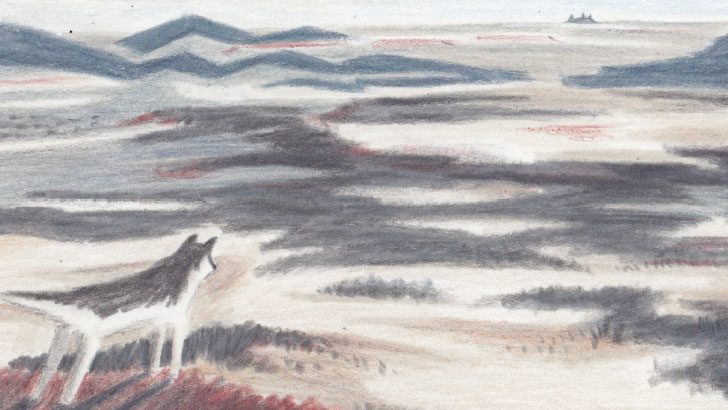

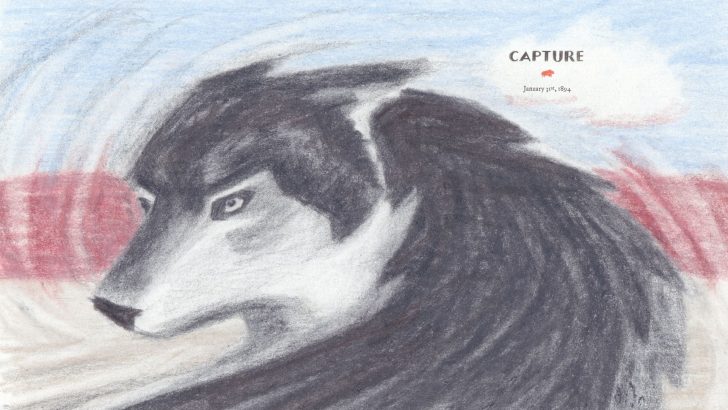

I think the story has a lot more impact when you know the context to it and what attitudes were like at the time. In a visual sense, travelling to Corrumpa Valley in New Mexico allowed me to take lots of first hand sketches and photos which influenced much of the artwork. Since wolves are no longer present there, I spent a week at a wolf sanctuary where I was able to draw wolves all morning. Simply drawing wolves at the sanctuary gave me lots of good reference for different postures and expressions which I tried to incorporate into the book.

4. Can you tell us more about your process? What comes first, the drawings or the words?

4. Can you tell us more about your process? What comes first, the drawings or the words?

They come hand in hand for me, it feels natural to make a list of important events while sketching out what spreads could look like. This helps me to visualize the book as a whole before I commit to the project. Colour is hugely important as it sets the tone of the book. I like to work up lots of colour swatches in the rough stages and see what colours work well together. Less is more as the saying goes, I think around six colours per book – more than that and things get messy!

Everything is hand drawn, the only digital aspect is moving spot illustrations on the page or adjusting colour levels slightly. This sounds nerdy, but I like Faber-Castell polychromos pencils, they have good strong pigments and a nice finish to them.

5. How long have you been working on The Wolves of Currumpaw? What were the most challenging and most rewarding parts?

About a year and a half, on and off, although the idea to re-interpret Seton’s text has been lingering in the back of my mind for longer. The most challenging thing for me was reducing the text to its most essential ingredients – this led to using small panels which felt quite new to me. Some of the large landscape pieces took repeated attempts which could be frustrating! Getting them right was a big relief.

6. When did you decide to be an illustrator, and who are you most influenced by?

When I was five I wanted to be a builder, I suppose it comes back to making things. I knew I wanted to draw for a living during my foundation year when I was about nineteen. Influences change all the time, but a few consistent people would be some of the Fauvist painters, Saul Steinberg, and the work of Eric Ravilious and Edward Bawden – their works have a really strong design aesthetic and have always had a particular charm to me. Recently I’ve been enjoying a lot of folk art, and stumbled upon the incredible work of Jivya Soma Mashe at the V&A Museum of Childhood.

7. It’s almost a year since you won the Kate Greenaway prize for Shackleton’s Journey! How did it feel to win? Do you have any plans to go into fiction, and can you tell us anything about what might be coming next?

It completely took me by surprise and still feels unreal to think I was chosen. It’s hugely encouraging to have the support from all the judges, although it now adds a little pressure to live up to the previous book!

I would like to venture into fiction at some point, although I’m enjoying non-fiction a lot at the moment. I think it would be interesting to try my hand at a darker subject matter in the future too. What really interests me though is blending genres and producing a book that is unusual. It’s hard to say what’s next at the minute as there are a few ideas floating about. I’m thinking it could be set somewhere green though, in a jungle or a forest perhaps.

8. What’s in your sketchbook at the moment? Can we take a look?

My sketchbook is in a display case at Waterstones Piccadilly right now for another three weeks so you can see them for real! I don’t have much else current but I visited Kew Gardens a while back and did a few chalk drawings there.

Thank you Will! Get a copy of the book here!